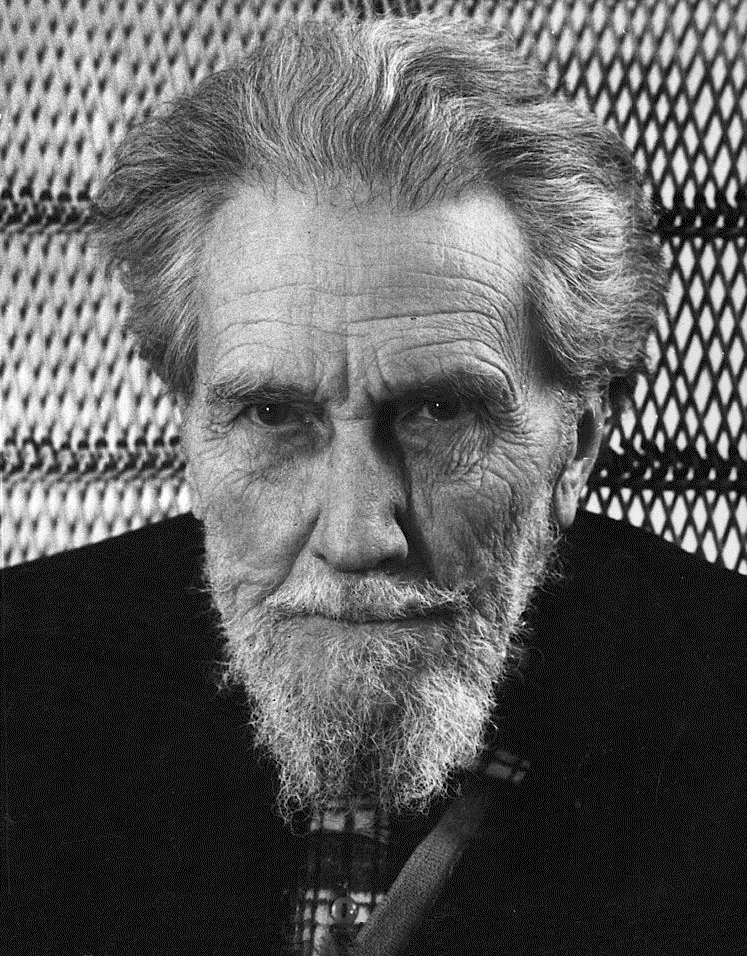

Jerome McGann wrote: “No English-speaking poet of this century has been the subject of as much biographical scrutiny as Ezra Pound.” Daniel Swift in the prologue to his biography of Pound adds that he was “the most difficult man of the 20th century”.

Since so much has been written about him – which you are encouraged to read – we will be brief .

The first charge against Pound is laid by McGann who says that it is not even clear that his poetry is indeed poetry. “The Cantos is a poem which, like De Rerum Natura, lays claim to what many regard as the province of prose, not poetry,” he writes. “Both reach out to make contact with extra-textual materials and events. Besides the poem’s engagement with history, including personal and contemporary history, much of the Cantos involves quotation (more or less accurately carried out) of historical documents, scholarly texts, and various independent and otherwise integral materials (a musical score is included as the major part of Canto LXXV).”

The second charge is related to the nature of much of Pound’s allusions and focus; because he was both an active fascist and anti-semite at a time when this was particularly egregious – during the Second World War.

As Robert Casillo put it, this illustrates very clearly ‘the problem of evil in literature’. Casillo’s great insight is that Pound’s fascism and anti-semitism are both central and pervasive to his work, not as his apologist’s have argued peripheral and separate. Casillo perceives anti-semitism as literally the key to reading and understanding Pound.

This you might dispute. But what nobody can deny is that between 1941 and 1943, Pound delivered pro-AXIS (ie pro Nazi) broadcasts four times a week (over 200 in total), denounced the Allies and attacked the Jews. He also enjoyed private audiences with Mussolini and was a eugenicist.

During his broadcasts he made statements such as: “‘I think it might be a good thing to hang Roosevelt [the US president at the time] and a few hundred yids if you can do it by due legal process”.

When the war ended he was charged with treason like his British counterpart Lord Haw-Haw (William Joyce). Unlike Joyce, who was the last person hanged in the UK for treason, Norway’s Vidkun Quisling, or France’s Pierre Laval, Pound got away with his crimes. Although the authorities wanted to prosecute him, his lawyers argued he was too mentally unwell to stand trial, while powerful admirers worked to arouse sympathy for his plight.

The argument ran that no one sane would have broadcast such virulent fascist propaganda (ignoring the fact that others did and later hanged for it) and that his poems were so incomprehensible they were evidence of his lunacy.

He remained, unremorseful, in a comfortable asylum (St Elizabeth’s) for the next 12 years. No-one made any attempt to treat him. He carried on writing and during the 50s began contributing opinion pieces which amongst other right wing themes regretted ‘the fuss about Hitler’. He considered Hitler ‘a martyr’, and said Mussolini was ‘a very human, imperfect character who lost his head’. Despite all of this he was given a nice room, books, a typewriter and a range of privileges, including after-hours conjugal visits (and not just with his wife).

While he was in ‘the bughouse’ (his nickname for St Elizabeth’s), major writers made regular pilgrimages to pay homage to him and seek his help with their work, bringing with them home comforts such as fudge brownies and cookies. These visitors included T.S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, Robert Lowell, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson, John Berryman, Louis Zukofsky, Elizabeth Bishop, W.S. Merwin, and Frederick Seidel.

He also began giving lectures on the lawn to an eager group of young disciples who called themselves ‘Ezrologists’.

All of which frustrated the authorities even more. In 1954, the US Attorney General wrote to the head of St Elizabeth’s querying why ‘this patient is mentally capable of translating and publishing poetry but not mentally capable of being brought to justice’.

The pressure to release him continued. And, after considerable campaigning by the literary elite, he was eventually released in 1958. He immediately returned to Italy, where he died in 1972.

Pound raises many questions about poetry and poets. Is his work really poetry, and, if so, does it have merit? Can poetry that contains unpalatable ideas really be regarded as ‘good’ poetry? Can poems be separated from the sins of their composer?

To find out more about Pound:

The Bughouse: The poetry, politics and madness of Ezra Pound by Daniel Swift.

The Genealogy of Demons: Anti-Semitism, Fascism, and the Myths of Ezra Pound by Robert Casillo.

Leave a Reply