The least well-known and most overlooked of the ‘Big Six’ Romantic Poets – William Blake, George Gordon Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Wordsworth – Samuel Taylor Coleridge was arguably the cleverest, most experimental and most erudite.

The Romantic fanboy, Thomas De Quincey, wrote in his Liverpool diary: ‘I begin to think him the greatest man that has ever appeared.’ De Quincey said that whenever Coleridge spoke it was as if he were tracing a circle in the air. (In other words he could go on and on, his intellectual diversions baffling and boring most people.) De Quincey was not most people, however.

Coleridge, like some great river, the Orellana, or the St Lawrence that, having been checked and fretted by rocks or thwarting islands, suddenly recovers its volume of waters and its mighty music, swept at once, as if returning to his natural business, into a continuous strain of eloquent dissertation, certainly the most novel, the most finely illustrated, and traversing the most spacious fields of thought by transitions the most just and logical, that it was possible to conceive.

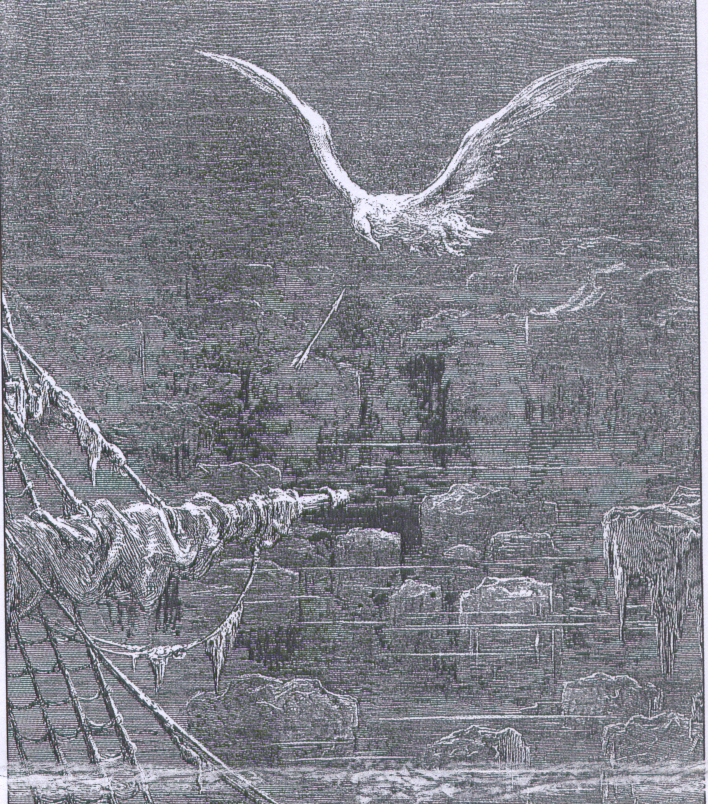

But what of his greatness as a poet? His poems often capture inner dream worlds, and are frequently dismissed as drug-induced hallucinations, because it’s undeniable that he took copious amounts of opium, providing the very template for the tortured, addicted poet. But The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is one of the best narrative poems ever written in English and Kubla Khan one of the most evocative and quotable.

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

Coleridge was not a bad poet – particularly after his collaborations with Wordsworth – but was he a bad man?

As we shall see, he was not only a bad husband but a worse father, and his addictions, obsessions and behaviour made him a very bad friend.

His wife – who even changed her Christian name at his insistence, dropping the ‘h’ – was born Sarah Fricker in 1770. She was one of the two Fricker sisters who Byron dimissively called ‘two milliners from Bath’ with the waspish tones of a Jane Austen novel. (Edith and Sarah had been forced to work as seamstresses after their father’s business failed.) But as he probably also knew, ‘milliner’ was eighteenth century slang for an immoral woman.

Sarah was a childhood friend of Robert Southey, who was already engaged to her sister Edith. After meeting Sarah, Coleridge wrote to Southey: ‘I certainly love her. I think of her incessantly and with unspeakable tenderness…’ That is not love, STC, it’s obsession and infatuation. Nevertheless, he wrote her a poem (The Kiss) and married her in 1795. By 1804, they were already separated.

Coleridge blamed Sarah – now Sara – for the separation, complaining that she was frigid: ‘all [is] as cold and calm as a deep frost’ [Notebooks 1:979]. But the truth was that he was not a man suited to the realities and responsibilities of everyday life and would have tested the patience of a saint. Expecting Sara to be a passionate lover on top of the many other services and duties she had to perform, as well as the things she had to put up with – such as his addiction, his constant illnesses and complaints, poverty and insecurity, being left to do all of the household work, bringing up the children alone, plus his infatuations – might easily be viewed as the height of selfishness. He wanted unbridled passion; she wanted to not get pregnant with yet another child he failed to support or bring up. He wanted attention; she wanted support.

In 1804 he left Sara and their three children to travel (for over 12 years) – to Italy, Malta, Sicily, the Lake District, Leicestershire and London – and the separation/abandonment saw her having to fall back on the goodwill of her sister and old friend Robert Southey (for the next 29 years).

Coleridge’s casual cruelty can be seen in Sara’s own words as early as 1798. He had planned a walking tour with the Wordsworths to Germany with the intention that Sara would join them. But the birth of their son, Berkeley, made this impossible. Of course, her pregnancy didn’t stop Coleridge from leaving for Germany. Then, in February 1799, Berkley died and Coleridge became distraught at the news.

Sara was not impressed, writing: ‘I am his mother, and have carried him in my arms and have fed him at my bosom, and have watched over him day and night for nine months: I have seen him twice at the brink of the grave but he has returned, and recovered and smiled upon me like an angel – and now I am lamenting that he is gone’. Coleridge didn’t rush home to comfort his wife – only returning to England in July, and then going to London rather than hurrying home to her.

Coleridge also (in)famously yearned for another Sara – Wordsworth’s sister-in-law, Sara Hutchinson – who was the ‘Asra’ of his poems. Note the spelling of her name, the childish anagram, and the timing of their first meeting (1799).

We know this betrayal – whether consummated or not – pained Sara Coleridge. She was excluded from the long country walks discussing poetry, inpiration and philosophy, because she had children to look after. There was more than a bit of snobbishness at play (on the part of Coleridge), who had come to despise his wife as being beneath him. Coleridge told Sara she had no right to be jealous. ‘That we can love but one person is a miserable mistake and the cause of abundant unhappiness,’ he wrote to her. Gaslighting at its finest.

Wordsworth, it seems, did not approve and there was something of a falling out between the two. From Coleridge’s Ad Vilmum Axiologum we can ascertain that Wordsworth rebuked his friend for his behaviour towards Sara Hutchinson. Then there was the much debated incident of Christmas 1806…

What we know is this. Coleridge and his son were staying with the Wordsworths for Christmas (they seemed to just turn up) and on the 27th December Coleridge went to Sara’s room (is this the reason he was rebuked?) where he saw something that caused him to literally run away in an hysterical fit. He was most probably under the effects of laudanum at this time, but what he saw, or fancied he saw, is now highly contentious.

This is what he wrote, or at least what survives, because he tore out and burnt the diary entries from this time:

O agony! O the vision of that Saturday morning! of the Bed – O cruel! is not he beloved, adored by two – & two such Beings. – And must I not be beloved near him except as a Satellite? – But O mercy, mercy! Is he not better, greater, more manly, & altogether more attractive to any but the purest Woman? And yet, he does not pretend, he does not wish, to love you as I love you, Sara! [September 1807]

O that miserable Saturday morning! …But a minute and a half with ME and all the time evidently restless & going – An hour and more with Wordsworth – in bed – O agony! [May 1808]

Some believe that Coleridge saw Sara in bed with Wordsworth. A more prosaic reading of this is that it is pure jealousy. Sara paid more attention to Wordsworth than to him [Coleridge] and it’s not fair because he (Wordsworth) already had his wife and Mary fussing over him. It’s certainly not clear from the surviving writing whether Coleridge perceived her to be in bed with Wordsworth or, more likely, Coleridge was in bed in agony (whether physical, emotional or both). What is clear is that Sara was actively avoiding him – ‘restless & going’ – and using Wordsworth as a chaperone, something most women subjected to unwanted attentions can relate to.

And then there were the drugs.

In Coleridge’s defence, his use of laudanum was neither illegal nor (initially) unnecessary. This potent mixture of opium and alcohol, which contains both morphine and codeine, was a common treatment for pain, as well as a wide range of other ills.

He was likely given it as a child and then again when he had rheumatic fever in 1790. In 1791 he explained in a letter to his brother George that he was still suffering from rheumatic ailments and had to take laudanum. By March 1796, he admits to taking it ‘almost every night’ and later that year says he was consuming 25 drops every five hours (this is very little compared to his peak usage).

1796 seems to be when his use of laudanum morphed into something else. By November he wrote to Thomas Poole that it inspired him, and the following year he told John Thelwall how he wished to: ‘float about along an infinite ocean cradled in the flower of the Lotos’. Although in 1804, he declared that he had never taken the drug for pleasure, only for pain control.

He may already have been addicted by 1796, but maintained later that this only occured around 1800 when he had another recurrence of his rheumatic problems that rendered him bed-ridden for months. He apparently learnt from a medical journal that laudanum could cure his affliction; but soon found himself in the vicious grip of addiction and began having horrible nightmares. One was a ghastly vision of Dorothy Wordsworth ‘altered in every feature…fat, thick-limbed’.

His admission of these nightmares renders him a completely unreliable narrator of the events of Christmas 1806. His surviving words, in any case, are vague and open to interpretation. Likewise, a week after his hysterical incident, he was sitting in the kitchen with Wordsworth, his wife, Dorothy and Sara Hutchinson to listen to a reading from the Prelude.

By the time Coleridge died from heart failure in 1834 – no doubt at least in part brought about by years of opium addiction – his life bore more than a passing resemblance to that of his Ancient Mariner. He had become increasingly unreliable between 1810 and 1816. He gave lectures at the Philosophical Institution which were sometimes terrible, late and disorganised and other times brilliant, although his famous long-windedness and penchant for digressions resurfaced even on the best of days.

When asked to translate Faust by John Murray in 1814, he failed to deliver. Whether he ever completed the translation is unknown, but in 2007 the Oxford University Press added to the mystery by declaring a translation first published in 1821 as being the lost Coleridge translation.

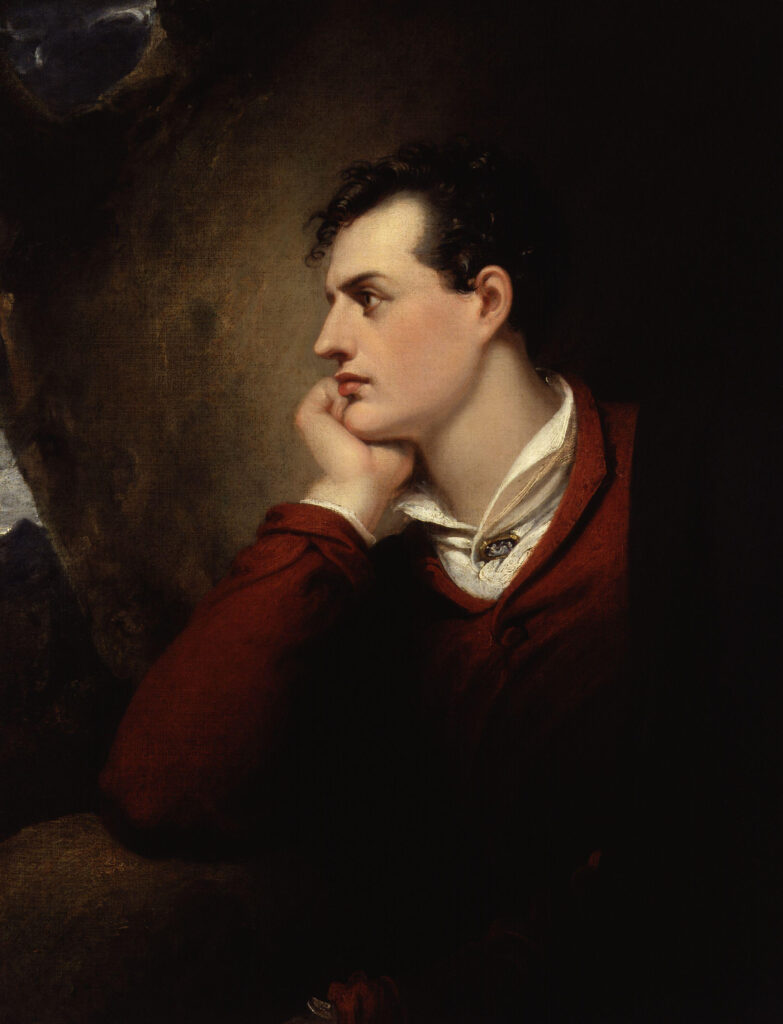

Many poets have admired his work, including Lord Byron. In 1815, he was moved to write to STC after Walter Scott had recited to him an unpublished poem by Coleridge.

Last Spring I saw W[alte]r Scott – he repeated to me a considerable portion of an unpublished poem of yours – the wildest & finest I ever heard in that kind of composition…all took a hold on my imagination which I never shall wish to shake off…W[alte]r Scott is a staunch & sturdy admirer of yours – & with a just appreciation of your capacity…

Byron adds that he is anxious to have a completed version of Coleridge’s tragedy, saying ‘I do not wish to hurry you – but I am indeed very anxious to have it under consideration – it is a field in which there are none living to contend against you & in which I should take a pride & pleasure in seeing you compared with the dead’.

The great irony of Coleridge is that greater tolerance and understanding had meant that his reputation, life and legacy were actively being reassessed – with critics arguing that not only was he a great lyrical poet, but that his poetry foreshadowed the Existentialist movement – with his depressive tendencies, constant pain, addictions and illnesses seen in a less judgemental light than the Victorians viewed him.

Only for him to now have fallen foul of modern sensibilities once again, because of his dire treatment of his wife.

Maybe Coleridge’s greatest role is to play the imperfect poet to perfection. A man of inconsistency and addiction, of vision, intellect and talent, that nevertheless was selfish, unreliable, egotistical and sometimes cruel. He suffered as much as he caused suffering. But perhaps his greatest lesson surfaces in a letter written when he was 22, where he reveals his depression, disappointments in love and his plan to ‘bid farewell forever’ to writing.

How many would-be writers have suffered the same angst? Should you suffer the same feeling, remember that Coleridge’s greatest poems were ahead of him.

“Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.”

Leave a Reply