Literary history is littered with scandalous figures, but few rival Algernon Charles Swinburne for sheer gothic excess. A poet of unmistakable musicality, Swinburne combined lush lyricism with a personal life straight out of a nightmare – one soaked in brandy, monkey carcasses, and unnerving erotic perversions.

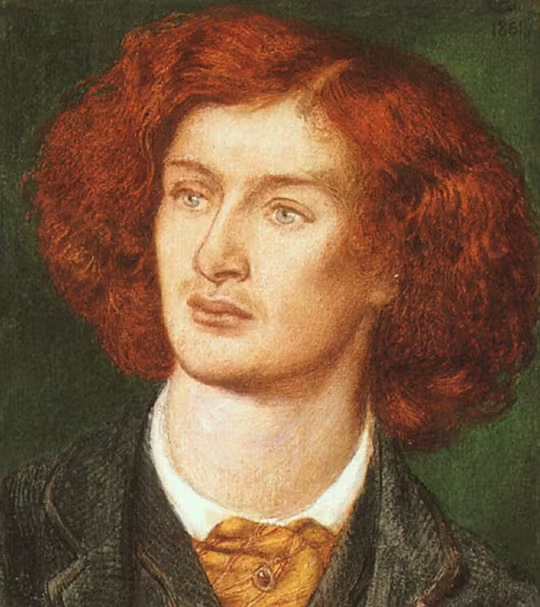

Born in 1837, Swinburne was a key figure in Pre-Raphaelite circles, living much of his adult life under the care (or surveillance) of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He was a small man with wild hair, a penchant for flagellation, and a deeply unhealthy relationship with alcohol. When not drunk, he was writing verses steeped in sadomasochism, cannibalism, and taboo passions. His poetry dances between the ethereal and the grotesque – and so did his life.

The French writer Guy de Maupassant once visited Swinburne, and the tale of what happened next is almost too lurid to be believed. He was reportedly shown a collection of illegal pornography, served monkey meat for lunch, and treated to a scene in which Swinburne’s lover, also sleeping with a pet monkey, played with a flayed human hand. Maupassant, apparently unfazed, returned a few days later. This time, the monkey was hanging (dead) from a tree and someone was taking potshots at a black man in the garden.

It reads like a scene from a lost Penny Dreadful, or a decadent horror penned by Baudelaire’s more depraved cousin.

And yet – amid this chaos – Swinburne wrote lines like these:

Yea, thou shalt be forgotten like spilt wine,

Except these kisses of my lips on thine

Brand them with immortality; but me –

Men shall not see bright fire nor hear the sea,

Nor mix their hearts with music, nor behold

Cast forth of heaven, with feet of awful gold

And plumeless wings that make the bright air blind…

Swinburne wrote like someone perpetually on the brink of delirium, tumbling through ancient myth, carnal pleasure, and existential dread. His mastery of rhythm, sound, and sensuality almost overwhelming – a torrent of beauty unmoored and unrestrained – reading him can feel like drowning in velvet.

But here’s the uncomfortable question: can poetic brilliance redeem personal depravity? Swinburne not only wrote about sadomasochism and pederasty – he openly boasted about indulging in them. His themes weren’t simply aesthetic provocations: they mirrored his obsessions. Unlike his contemporary Oscar Wilde, whose queerness was criminalised but whose wit remains luminous, Swinburne gleefully skated into darker territory, muddying art and ethics.

Perhaps that’s why his reputation remains in limbo. Too talented to forget, too unsettling to celebrate uncritically. Swinburne is the sort of literary figure quietly shelved next to the liquour cabinet and humidor. One most definitely not discussed in polite company.

And yet, there he is – immortal, if not redeemable, in lines of devastating beauty.

So: do lush rhymes make up for pederasty? No. But they do complicate how we reckon with genius when it’s wrapped in unacceptable behaviour. Swinburne forces us to confront the moral tension between art and artist – and to ask, uncomfortably, where we draw the line between brilliance and monstrosity.

Leave a Reply